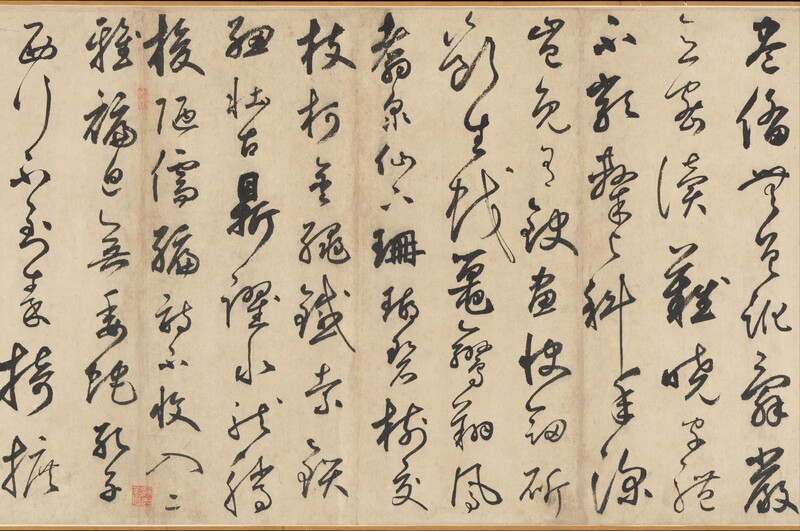

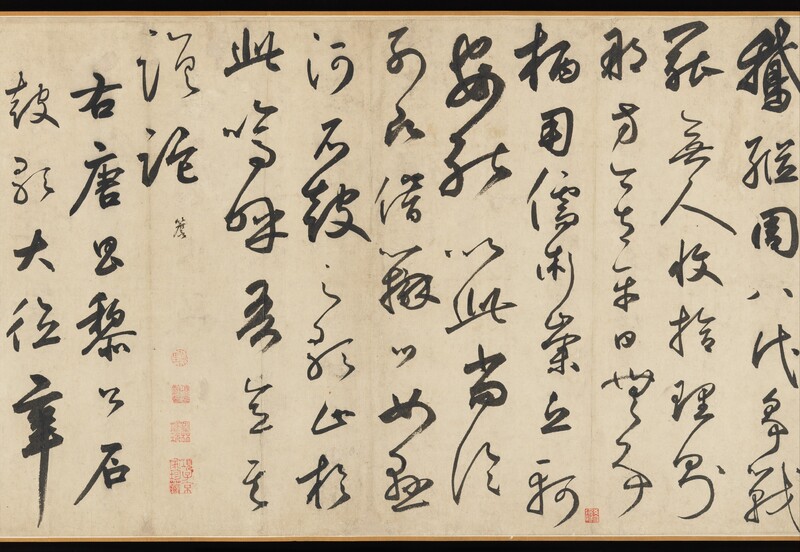

Song of the Stone Drums 草書石鼓歌

Item

Title

Song of the Stone Drums

草書石鼓歌

草書石鼓歌

Description

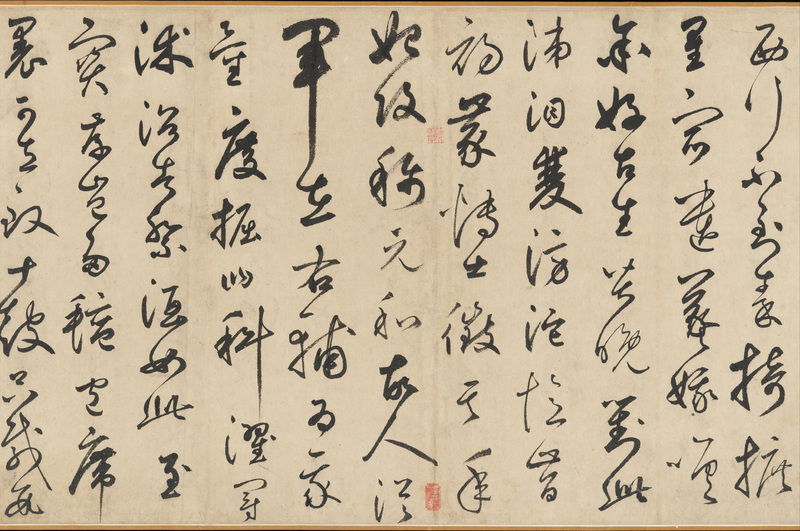

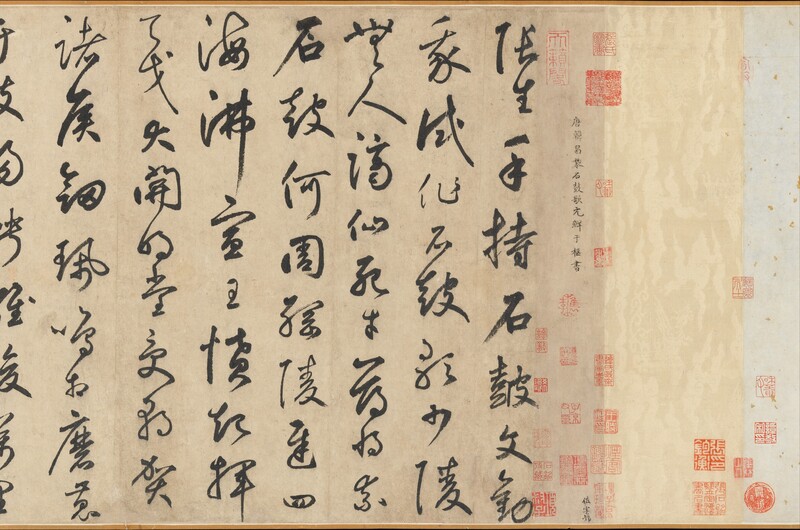

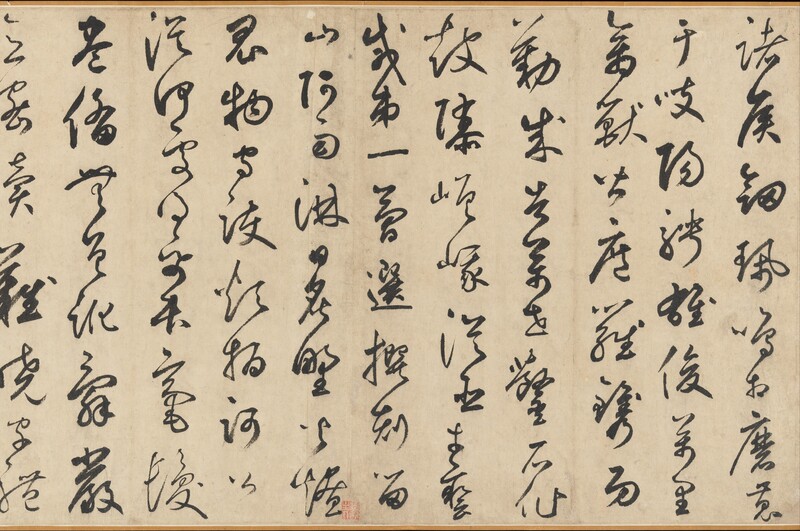

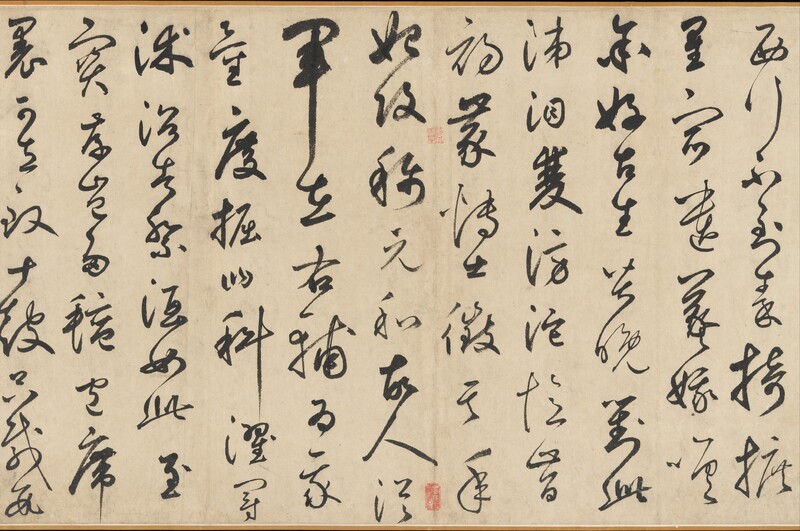

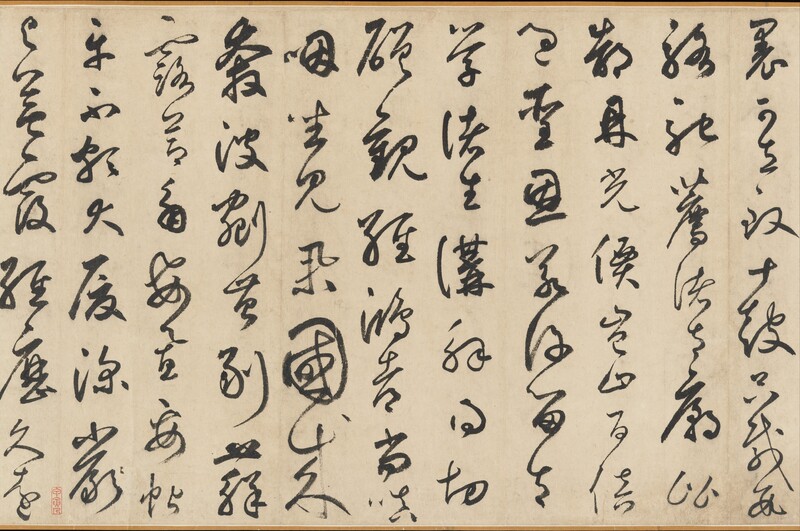

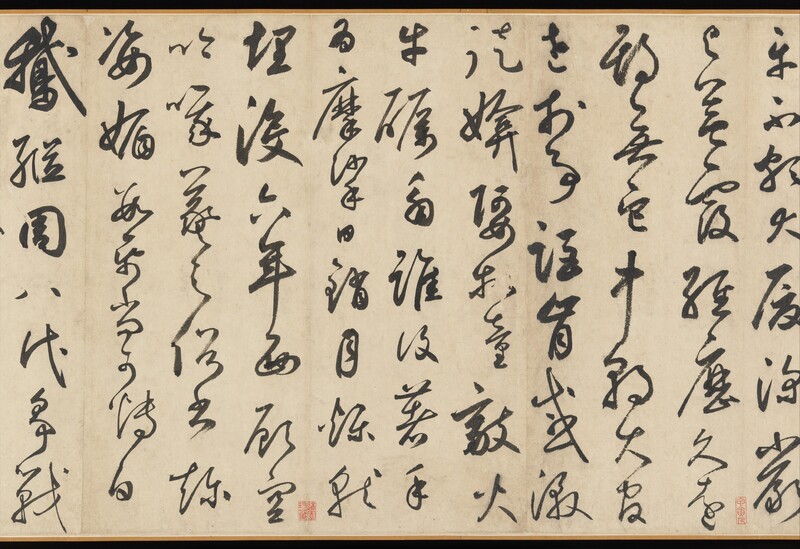

Artist’s inscription and signature (68 columns in cursive script)

Zhang handed me this tracing, from the stone drums,

Beseeching me to write a poem on the stone drums.

Du Fu has gone. Li Bo is dead.

What can my poor talent do for the stone drums?

…When the Zhou power waned and China was bubbling,

Emperor Xuan, up in wrath, waved his holy spear

And opened his Great Audience, receiving all the tributes

Of kings and lords who came to him with a tune of clanging weapons.

They held a hunt in Qiyang and proved their marksmanship:

Fallen birds and animals were strewn three thousand miles.

And the exploit was recorded, to inform new generations…

Cut out of jutting cliffs, these drums made of stone –

On which poets and artisans, all of the first order,

Had indited and chiseled – were set into the deep mountains

To be washed by rain, baked by sun, burned by wildfire,

Eyed by evil spirits, and protected by the gods.

…Where can he have found the tracing on this paper? –

True to the original, not altered by a hair,

The meaning deep, the phrases cryptic, difficult to read,

And the style of the characters neither square nor tadpole.

Time has not yet vanquished the beauty of these letters –

Looking like sharp daggers that pierce live crocodiles,

Like phoenix–mates dancing, like angels hovering down,

Like trees of jade and coral with interlocking branches,

Like golden cord and iron chain tied together tight,

Like incense-tripods flung in the sea, like dragons mounting heaven.

Historians, gathering ancient poems, forgot to gather these,

To make the two Books of Musical Song more colorful and striking;

Confucius journeyed in the west, but not to the Qin Kingdom,

He chose our planet and our stars but missed the sun and moon…

I who am fond of antiquity, was born too late

And, thinking of these wonderful things, cannot hold back my tears…

I remember, when I was awarded my highest degree,

During the first year of Yuanhe,

How a friend of mine, then at the western camp,

Offered to assist me in removing these old relics.

I bathed and changed, then made my plea to the college president

And urged on him the rareness of these most precious things.

They could be wrapped in rugs, be packed and sent in boxes

And carried on only a few camels: ten stone drums

To grace the Imperial Temple like the Incense-Pot of Gao –

Or their lustre and their value would increase a hundredfold,

If the monarch would present them to the university,

Where students could study them and doubtless decipher them,

And multitudes, attracted to the capital of culture

From all corners of the Empire, would be quick to gather.

We could scour the moss, pick out the dirt, restore the original surface,

And lodge them in a fitting and secure place for ever,

Covered by a massive building with wide eaves

Where nothing more might happen to them as it had before.

…But government officials grow fixed in their ways

And never will initiate beyond precedent;

So herd-boys strike the drums for fire, cows polish horns on them,

With no one to handle them reverentially.

Still aging and decaying, soon they may be effaced.

Six years I have sighed for them, chanting toward the west...

The familiar script of Wang Xizhi, beautiful though it was,

Could be had, several pages, for a few white geese!

But not, eight dynasties after the Zhou, and all the wars over,

Why should there be nobody caring for these drums?

The empire is at peace, the government free.

Poets again are honored and Confucians and Mencians…

Oh, how may this petition be carried to the throne?

It needs indeed an eloquent flow, like a cataract –

But, alas, my voice has broken, in my song of the stone drums,

To a sound of supplication choked with its own tears.[1]

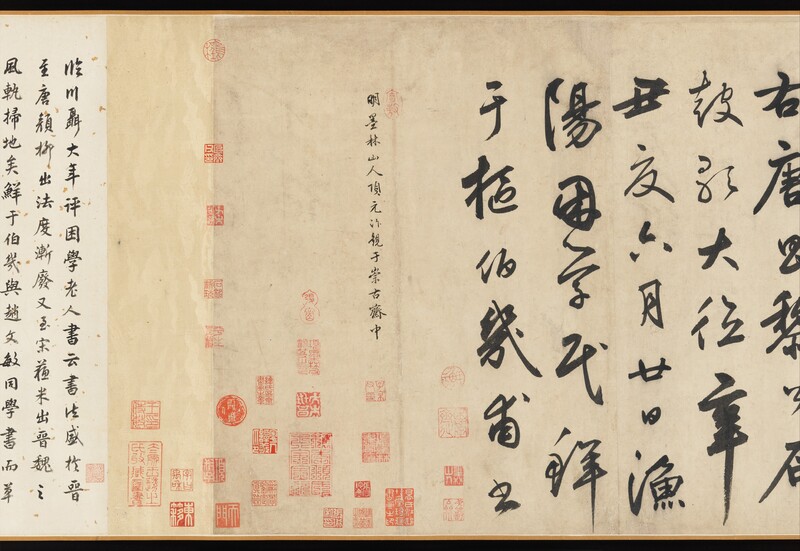

To the right is “Song of the Stone Drums” composed by Changli [Han Yu, 768–824] of the Tang dynasty. Written by Kunxuemin, Xianyu Shu, Boji from Yuyang [present-day Jixian, Hebei] in the summer, the twentieth of the sixth lunar month, of the xinchou year in the Dade reign era [July 26, 1301].

張生手持石鼓文,勸我試作石鼓歌。

少陵無人謫仙死,才薄將奈石鼓何。

周綱陵遲四海沸,宣王憤起揮天戈。

大開明堂受朝賀,諸侯劒珮鳴相磨。

蒐于岐陽騁雄俊,萬里禽獸皆庶羅。

鐫功勒成告萬世,鑿石作鼓隳嵯峨。

從臣才藝咸第一,簡選撰刻留山阿。

雨淋日炙野火燎,鬼物守護煩撝訶。

公從何處得帋本,毫髮盡備無差訛。

辭嚴意密讀難曉,字體不類隸與科[蝌]。

年深豈免有缺畫,快劒斫斷生蛟鼉。

鸞翔鳳翥眾仙下,珊瑚碧樹交枝柯。

金繩鐵索鎖紐壯,古鼎躍水龍騰梭。

陋儒編詩不收入,二雅褊迫無委蛇。

孔子西行不到秦,掎摭星宿遺羲娥。

嗟余好古生苦晚,對此涕泪雙滂沱。

憶昔初蒙博士徵,其年始改稱元和。

故人從軍在右輔,為我量度[度量]掘臼科。

濯冠沐浴告祭酒,如此至寶存豈多。

氈包席裹可立致,十鼓只載數駱駝。

薦諸太廟比郜鼎,光價豈止百倍過。

聖恩若許留太學,諸生講解得切磋。

觀經鴻都尚嗔咽,坐見擧國來奔波。

剜苔剔蘚露節角,安置妥帖平不頗。

大廈深巖[點去]與蓋覆,經歷久遠期無它[佗]。

中朝大官老於事,詎肯感激徒媕婀。

牧童敲火牛礪角,誰復著手為摩挲。

日銷月爍就埋沒,六年西顧空吟哦。

羲之俗書趁姿媚,數帋尚可愽白鹅。

繼周八代爭戰罷,無人收拾理則那。

方今太平日無事,柄用儒術崇丘軻。

安能以此尚論列,願借辯口如懸河。

石鼓之歌止於此,嗚呼吾意其蹉跎。簷

右唐昌黎公 〈石鼓歌〉。大德辛丑夏六月廿日漁陽困學民鮮于樞伯幾甫書。

Artist's seals

Xianyu 鮮于

Kunxue Zhai 困學齋

[1] Translation from Witter Bynner and Kiang Kang-hu, The Jade Mountain: A Chinese Anthology. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1931, pp. 33-35. The Romanization has been changed from Wade-Giles to pingyin.

Zhang handed me this tracing, from the stone drums,

Beseeching me to write a poem on the stone drums.

Du Fu has gone. Li Bo is dead.

What can my poor talent do for the stone drums?

…When the Zhou power waned and China was bubbling,

Emperor Xuan, up in wrath, waved his holy spear

And opened his Great Audience, receiving all the tributes

Of kings and lords who came to him with a tune of clanging weapons.

They held a hunt in Qiyang and proved their marksmanship:

Fallen birds and animals were strewn three thousand miles.

And the exploit was recorded, to inform new generations…

Cut out of jutting cliffs, these drums made of stone –

On which poets and artisans, all of the first order,

Had indited and chiseled – were set into the deep mountains

To be washed by rain, baked by sun, burned by wildfire,

Eyed by evil spirits, and protected by the gods.

…Where can he have found the tracing on this paper? –

True to the original, not altered by a hair,

The meaning deep, the phrases cryptic, difficult to read,

And the style of the characters neither square nor tadpole.

Time has not yet vanquished the beauty of these letters –

Looking like sharp daggers that pierce live crocodiles,

Like phoenix–mates dancing, like angels hovering down,

Like trees of jade and coral with interlocking branches,

Like golden cord and iron chain tied together tight,

Like incense-tripods flung in the sea, like dragons mounting heaven.

Historians, gathering ancient poems, forgot to gather these,

To make the two Books of Musical Song more colorful and striking;

Confucius journeyed in the west, but not to the Qin Kingdom,

He chose our planet and our stars but missed the sun and moon…

I who am fond of antiquity, was born too late

And, thinking of these wonderful things, cannot hold back my tears…

I remember, when I was awarded my highest degree,

During the first year of Yuanhe,

How a friend of mine, then at the western camp,

Offered to assist me in removing these old relics.

I bathed and changed, then made my plea to the college president

And urged on him the rareness of these most precious things.

They could be wrapped in rugs, be packed and sent in boxes

And carried on only a few camels: ten stone drums

To grace the Imperial Temple like the Incense-Pot of Gao –

Or their lustre and their value would increase a hundredfold,

If the monarch would present them to the university,

Where students could study them and doubtless decipher them,

And multitudes, attracted to the capital of culture

From all corners of the Empire, would be quick to gather.

We could scour the moss, pick out the dirt, restore the original surface,

And lodge them in a fitting and secure place for ever,

Covered by a massive building with wide eaves

Where nothing more might happen to them as it had before.

…But government officials grow fixed in their ways

And never will initiate beyond precedent;

So herd-boys strike the drums for fire, cows polish horns on them,

With no one to handle them reverentially.

Still aging and decaying, soon they may be effaced.

Six years I have sighed for them, chanting toward the west...

The familiar script of Wang Xizhi, beautiful though it was,

Could be had, several pages, for a few white geese!

But not, eight dynasties after the Zhou, and all the wars over,

Why should there be nobody caring for these drums?

The empire is at peace, the government free.

Poets again are honored and Confucians and Mencians…

Oh, how may this petition be carried to the throne?

It needs indeed an eloquent flow, like a cataract –

But, alas, my voice has broken, in my song of the stone drums,

To a sound of supplication choked with its own tears.[1]

To the right is “Song of the Stone Drums” composed by Changli [Han Yu, 768–824] of the Tang dynasty. Written by Kunxuemin, Xianyu Shu, Boji from Yuyang [present-day Jixian, Hebei] in the summer, the twentieth of the sixth lunar month, of the xinchou year in the Dade reign era [July 26, 1301].

張生手持石鼓文,勸我試作石鼓歌。

少陵無人謫仙死,才薄將奈石鼓何。

周綱陵遲四海沸,宣王憤起揮天戈。

大開明堂受朝賀,諸侯劒珮鳴相磨。

蒐于岐陽騁雄俊,萬里禽獸皆庶羅。

鐫功勒成告萬世,鑿石作鼓隳嵯峨。

從臣才藝咸第一,簡選撰刻留山阿。

雨淋日炙野火燎,鬼物守護煩撝訶。

公從何處得帋本,毫髮盡備無差訛。

辭嚴意密讀難曉,字體不類隸與科[蝌]。

年深豈免有缺畫,快劒斫斷生蛟鼉。

鸞翔鳳翥眾仙下,珊瑚碧樹交枝柯。

金繩鐵索鎖紐壯,古鼎躍水龍騰梭。

陋儒編詩不收入,二雅褊迫無委蛇。

孔子西行不到秦,掎摭星宿遺羲娥。

嗟余好古生苦晚,對此涕泪雙滂沱。

憶昔初蒙博士徵,其年始改稱元和。

故人從軍在右輔,為我量度[度量]掘臼科。

濯冠沐浴告祭酒,如此至寶存豈多。

氈包席裹可立致,十鼓只載數駱駝。

薦諸太廟比郜鼎,光價豈止百倍過。

聖恩若許留太學,諸生講解得切磋。

觀經鴻都尚嗔咽,坐見擧國來奔波。

剜苔剔蘚露節角,安置妥帖平不頗。

大廈深巖[點去]與蓋覆,經歷久遠期無它[佗]。

中朝大官老於事,詎肯感激徒媕婀。

牧童敲火牛礪角,誰復著手為摩挲。

日銷月爍就埋沒,六年西顧空吟哦。

羲之俗書趁姿媚,數帋尚可愽白鹅。

繼周八代爭戰罷,無人收拾理則那。

方今太平日無事,柄用儒術崇丘軻。

安能以此尚論列,願借辯口如懸河。

石鼓之歌止於此,嗚呼吾意其蹉跎。簷

右唐昌黎公 〈石鼓歌〉。大德辛丑夏六月廿日漁陽困學民鮮于樞伯幾甫書。

Artist's seals

Xianyu 鮮于

Kunxue Zhai 困學齋

[1] Translation from Witter Bynner and Kiang Kang-hu, The Jade Mountain: A Chinese Anthology. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1931, pp. 33-35. The Romanization has been changed from Wade-Giles to pingyin.

identifier

40512

Source

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/40512

Creator

Xianyu Shu

鮮于樞

鮮于樞

annotates

Label strip

Shen Yinmo 沈尹默 (1882–1971), 2 column in semi-cursive script, undated; 1 seal:

Song of the Stone Drums written in cursive script by Xianyu Boji [Xianyu Shu] of the Yuan dynasty, inscribed at the request of my venerable friend Congyu [Zhang Heng, 1915–1963], Yinmo. [Seal]: Shen

元鮮于伯幾草書 《石鼓歌》,葱玉尊兄屬題,尹默。 [印]: 沈

Colophons[2]

1. Xiang Yuanbian 項元汴 (1525–1590), 1 column in standard script, undated (preceding the text):

“Song of the Stone Drums” composed by Han Changli [Han Yu, 768–824] of the Tang dynasty, transcribed by Xianyu Shu of the Yuan dynasty.

唐韓昌黎 《石鼓歌》,元鮮于樞書。

2. Xiang Yuanbian 項元汴 (1525–1590), inventory character, 1 column in standard script, undated (preceding the text):

Zuo zi hao

佐字號

3. Xiang Yuanbian 項元汴 (1525–1590), 1 column in standard script, undated:

Molin Shanren, Xiang Yuanbian, of the Ming dynasty viewed this in Chonggu Zhai [Revering Antiquity Studio].

明墨林山人項元汴觀于崇古齋中。

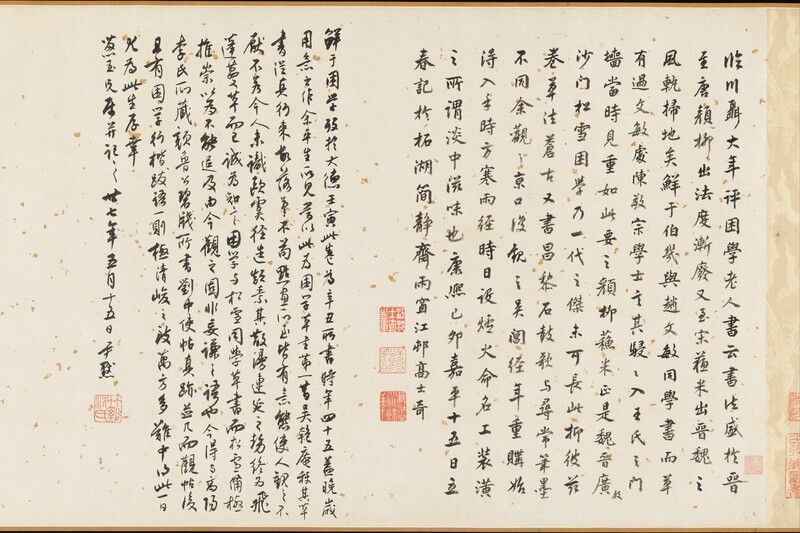

4. Gao Shiqi 高士奇 (1654–1704), 11 columns in semi-cursive script, dated 1700; 3 seals:

Nie Danian (1402–1456) of Linchuan comments on the calligraphy of Kunxue Laoren [Xianyu Shu] stating: “Calligraphy flourished in the Jin period (317–419). In the Tang dynasty, with the rise of Yan [Zhenqing, 709–785] and Liu [Gongquan, 778–865], the methods and criteria of the old tradition gradually deteriorated. When the style of Su [Shi, 1037–1101] and Mi [Fu, 1052–1107] appeared in the Song dynasty, the tradition of the Wei and Jin periods was then completely discarded. Xianyu Boji [Xianyu Shu] studied calligraphy together with Zhao Wenmin [Zhao Mengfu, 1254–1322]. But there are qualities in his cursive script that surpass Zhao Mengfu.” Chen Jingzong (1377–1459), the academician, once remarked that [Xianyu Shu’s calligraphy] has definitely entered the gate of the Wang [Xizhi school]. So highly was he regarded by his contemporaries. In short, if one considers the masters Yan, Liu, Su, and Mi as missionaries of the [calligraphic] cult of Wei-Jin, then Zhao Songxue [Zhao Mengfu] and Xianyu Kunxue [Xianyu Shu] were the most outstanding artists of their times. One therefore should not be biased against one at the expense of the other. The cursive style of this scroll has an aged quality of maturity, in addition to the fact that it transcribes Han Yu’s “Song of the Stone Drums.” It is certainly not in the same order as the artist’s more ordinary works. I first saw the scroll in Jingkou, then again in Suzhou. For years I have tried to acquire it before it finally came into my possession. That was the time when we had a continuous cold rain, and I had to keep the stove fire burning every day so the scroll could be remounted by a famed restorer. This is indeed the kind of life that people call “the tasting out of the tasteless.”[3] On the fifteenth of jiaping [the twelfth lunar month] in the jimao year of the Kangxi reign era [February 3, 1700], at the beginning of spring, Gao Shiqi, Jiangcun, noted this by a rainy window in the Jianjing Zhai Studio at Zhehu. [Seals]: Hao zhuangxin qian yunian, Bu yi sangong yi ciri, Jiangcun Shiqi zhi zhang

臨川聶大年評困學老人書云:“書法盛於晉,至唐顏、柳出,法度漸廢。又至宋蘇、米出,晉、魏之風軌掃地矣。鮮于伯幾與趙文敏同學書,而草有過文敏處。”陳敬宗學士言其駸駸入王氏之門墻,當時見重如此。要之顏、柳、蘇、米正是魏晉廣教沙門,松雪、困學乃一代之傑,未可長此抑彼。玆卷草法蒼古,又書昌黎〈石鼓歌〉,與尋常筆墨不同。余觀之京口,復觀之吳閶,經年重購,始得入手,時方寒雨經時,日設爐火,命名工裝潢之,所謂淡中滋味也。康熙己卯嘉平十五日立春記於柘湖簡靜齋雨窗,江邨高士奇。 [印]: 耗壯心遣餘年、不以三公易此日、江邨士奇之章

5. Shen Yinmo 沈尹默 (1882–1971), 10 columns in semi-cursive script, dated 1938; 1 seal:

Xianyu Kunxue [Xianyu Shu] died in the renyin year of the Dade reign era [1302]. This scroll was written in the xinchou year [1301] when the artist was forty-five years old. It is therefore a work of great deliberation done in his mature years. Among his works that I have seen, this probably ranks highest among [examples of] his cursive script. Wu Pao An [Wu Kuan, 1435–1504] used to say that “Xianyu Shu’s cursive script was derived from the methods of the standard and semi-cursive scripts. The brush was applied with great care. As a result there is always a particular logic and deportment in each of his dots and strokes which never make his audience feel bored or tired. People these days like to reach out for the attainment of Zhang Xu (ca. 675–ca. 750) and [Huai] Su [ca. 735–ca. 800] before they even know anything about the older masters, Ouyang Xun (557–641) and Yu Shinan (558–638). That is why the structure of their calligraphy is so loose, incoherent, and so torturously long-winded that they end up nothing much more than pieces of blown away thatch of creeping weeds.” This is indeed well said. Xianyu Kunxue studied the cursive script together with Zhao Songxue [Zhao Mengfu, 1254–1322]. Zhao could not praise him more highly, conceding that his art is unsurpassable. Judging from the present example, Zhao’s modesty was after all no mere lip service. Today, I am able to see this scroll side-by-side with the Liu Zhongshi tie, an authentic work written on a bluish paper by Yan Zhenqing from the collection of the Li family of Gaoyang. In addition, at the end of the scroll is Xianyu Shu’s own colophon written in semi-cursive/standard script which again is as fresh and lofty as in his best. It is surely one of the best fortunes of my life to be able to enjoy a day such as this amid all the turmoils boiling over everywhere. Recorded on request of my friend, Congyu [Zhang Heng, 1915–1963],[4] on May fifteenth in the twenty-seventh year [of the Republic] [1938], Yinmo. [Seal]: Zhuxi Shen shi

鮮于困學歿於大德壬寅,此卷為辛丑所書,時年四十五,蓋晚歲用意之作。余平生所見,當以此為困學草書第一。昔吳匏庵稱其草書從真行來買,故落筆不茍,點畫所至,皆有意態,使人觀之不厭。不若今人未識歐、虞,徑造顛、素,其散漫連延之勢終為飛蓬蔓草而已,誠為知言。困學與松雪同學草書,而松雪備極推崇,以為不能追及。由今觀之,固非妄謙之語也。今得與高陽李氏所藏顏魯公碧箋所書《劉中使帖》真跡並几而觀,帖後且有困學行楷跋語一則,極清峻之致。萬方多難中得此一日,尤為此生厚幸。葱玉兄屬并記之,廿七年五月十五日,尹默。 [印]: 竹谿沈氏

6. Xiang Yuan 項源 (active early 19th c.), 1 column in running/standard script, dated 1831; 2 seals:

Xiang Yuan from She [in Anhui Province] respectfully viewed this in the early summer of the xinmao year of the Daoguang reign era [1831]. [Seals]: Xiao Tianlai Ge, Xiang Yuan zi Hanquan yizi Zhifang

道光辛卯小暑歙項芝房敬觀。 [印]: 小天籟閣、項源字漢泉一字芝房

[2] Translations from Department records.

[3] Translation from Sherman E. Lee and Wai-kam ho, Chinese Art Under the Mongols: The Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368). Exh. cat. Cleveland, OH: The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1968, no. 274. Modified.

[4] Ibid. Modified.

Shen Yinmo 沈尹默 (1882–1971), 2 column in semi-cursive script, undated; 1 seal:

Song of the Stone Drums written in cursive script by Xianyu Boji [Xianyu Shu] of the Yuan dynasty, inscribed at the request of my venerable friend Congyu [Zhang Heng, 1915–1963], Yinmo. [Seal]: Shen

元鮮于伯幾草書 《石鼓歌》,葱玉尊兄屬題,尹默。 [印]: 沈

Colophons[2]

1. Xiang Yuanbian 項元汴 (1525–1590), 1 column in standard script, undated (preceding the text):

“Song of the Stone Drums” composed by Han Changli [Han Yu, 768–824] of the Tang dynasty, transcribed by Xianyu Shu of the Yuan dynasty.

唐韓昌黎 《石鼓歌》,元鮮于樞書。

2. Xiang Yuanbian 項元汴 (1525–1590), inventory character, 1 column in standard script, undated (preceding the text):

Zuo zi hao

佐字號

3. Xiang Yuanbian 項元汴 (1525–1590), 1 column in standard script, undated:

Molin Shanren, Xiang Yuanbian, of the Ming dynasty viewed this in Chonggu Zhai [Revering Antiquity Studio].

明墨林山人項元汴觀于崇古齋中。

4. Gao Shiqi 高士奇 (1654–1704), 11 columns in semi-cursive script, dated 1700; 3 seals:

Nie Danian (1402–1456) of Linchuan comments on the calligraphy of Kunxue Laoren [Xianyu Shu] stating: “Calligraphy flourished in the Jin period (317–419). In the Tang dynasty, with the rise of Yan [Zhenqing, 709–785] and Liu [Gongquan, 778–865], the methods and criteria of the old tradition gradually deteriorated. When the style of Su [Shi, 1037–1101] and Mi [Fu, 1052–1107] appeared in the Song dynasty, the tradition of the Wei and Jin periods was then completely discarded. Xianyu Boji [Xianyu Shu] studied calligraphy together with Zhao Wenmin [Zhao Mengfu, 1254–1322]. But there are qualities in his cursive script that surpass Zhao Mengfu.” Chen Jingzong (1377–1459), the academician, once remarked that [Xianyu Shu’s calligraphy] has definitely entered the gate of the Wang [Xizhi school]. So highly was he regarded by his contemporaries. In short, if one considers the masters Yan, Liu, Su, and Mi as missionaries of the [calligraphic] cult of Wei-Jin, then Zhao Songxue [Zhao Mengfu] and Xianyu Kunxue [Xianyu Shu] were the most outstanding artists of their times. One therefore should not be biased against one at the expense of the other. The cursive style of this scroll has an aged quality of maturity, in addition to the fact that it transcribes Han Yu’s “Song of the Stone Drums.” It is certainly not in the same order as the artist’s more ordinary works. I first saw the scroll in Jingkou, then again in Suzhou. For years I have tried to acquire it before it finally came into my possession. That was the time when we had a continuous cold rain, and I had to keep the stove fire burning every day so the scroll could be remounted by a famed restorer. This is indeed the kind of life that people call “the tasting out of the tasteless.”[3] On the fifteenth of jiaping [the twelfth lunar month] in the jimao year of the Kangxi reign era [February 3, 1700], at the beginning of spring, Gao Shiqi, Jiangcun, noted this by a rainy window in the Jianjing Zhai Studio at Zhehu. [Seals]: Hao zhuangxin qian yunian, Bu yi sangong yi ciri, Jiangcun Shiqi zhi zhang

臨川聶大年評困學老人書云:“書法盛於晉,至唐顏、柳出,法度漸廢。又至宋蘇、米出,晉、魏之風軌掃地矣。鮮于伯幾與趙文敏同學書,而草有過文敏處。”陳敬宗學士言其駸駸入王氏之門墻,當時見重如此。要之顏、柳、蘇、米正是魏晉廣教沙門,松雪、困學乃一代之傑,未可長此抑彼。玆卷草法蒼古,又書昌黎〈石鼓歌〉,與尋常筆墨不同。余觀之京口,復觀之吳閶,經年重購,始得入手,時方寒雨經時,日設爐火,命名工裝潢之,所謂淡中滋味也。康熙己卯嘉平十五日立春記於柘湖簡靜齋雨窗,江邨高士奇。 [印]: 耗壯心遣餘年、不以三公易此日、江邨士奇之章

5. Shen Yinmo 沈尹默 (1882–1971), 10 columns in semi-cursive script, dated 1938; 1 seal:

Xianyu Kunxue [Xianyu Shu] died in the renyin year of the Dade reign era [1302]. This scroll was written in the xinchou year [1301] when the artist was forty-five years old. It is therefore a work of great deliberation done in his mature years. Among his works that I have seen, this probably ranks highest among [examples of] his cursive script. Wu Pao An [Wu Kuan, 1435–1504] used to say that “Xianyu Shu’s cursive script was derived from the methods of the standard and semi-cursive scripts. The brush was applied with great care. As a result there is always a particular logic and deportment in each of his dots and strokes which never make his audience feel bored or tired. People these days like to reach out for the attainment of Zhang Xu (ca. 675–ca. 750) and [Huai] Su [ca. 735–ca. 800] before they even know anything about the older masters, Ouyang Xun (557–641) and Yu Shinan (558–638). That is why the structure of their calligraphy is so loose, incoherent, and so torturously long-winded that they end up nothing much more than pieces of blown away thatch of creeping weeds.” This is indeed well said. Xianyu Kunxue studied the cursive script together with Zhao Songxue [Zhao Mengfu, 1254–1322]. Zhao could not praise him more highly, conceding that his art is unsurpassable. Judging from the present example, Zhao’s modesty was after all no mere lip service. Today, I am able to see this scroll side-by-side with the Liu Zhongshi tie, an authentic work written on a bluish paper by Yan Zhenqing from the collection of the Li family of Gaoyang. In addition, at the end of the scroll is Xianyu Shu’s own colophon written in semi-cursive/standard script which again is as fresh and lofty as in his best. It is surely one of the best fortunes of my life to be able to enjoy a day such as this amid all the turmoils boiling over everywhere. Recorded on request of my friend, Congyu [Zhang Heng, 1915–1963],[4] on May fifteenth in the twenty-seventh year [of the Republic] [1938], Yinmo. [Seal]: Zhuxi Shen shi

鮮于困學歿於大德壬寅,此卷為辛丑所書,時年四十五,蓋晚歲用意之作。余平生所見,當以此為困學草書第一。昔吳匏庵稱其草書從真行來買,故落筆不茍,點畫所至,皆有意態,使人觀之不厭。不若今人未識歐、虞,徑造顛、素,其散漫連延之勢終為飛蓬蔓草而已,誠為知言。困學與松雪同學草書,而松雪備極推崇,以為不能追及。由今觀之,固非妄謙之語也。今得與高陽李氏所藏顏魯公碧箋所書《劉中使帖》真跡並几而觀,帖後且有困學行楷跋語一則,極清峻之致。萬方多難中得此一日,尤為此生厚幸。葱玉兄屬并記之,廿七年五月十五日,尹默。 [印]: 竹谿沈氏

6. Xiang Yuan 項源 (active early 19th c.), 1 column in running/standard script, dated 1831; 2 seals:

Xiang Yuan from She [in Anhui Province] respectfully viewed this in the early summer of the xinmao year of the Daoguang reign era [1831]. [Seals]: Xiao Tianlai Ge, Xiang Yuan zi Hanquan yizi Zhifang

道光辛卯小暑歙項芝房敬觀。 [印]: 小天籟閣、項源字漢泉一字芝房

[2] Translations from Department records.

[3] Translation from Sherman E. Lee and Wai-kam ho, Chinese Art Under the Mongols: The Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368). Exh. cat. Cleveland, OH: The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1968, no. 274. Modified.

[4] Ibid. Modified.

Abstract

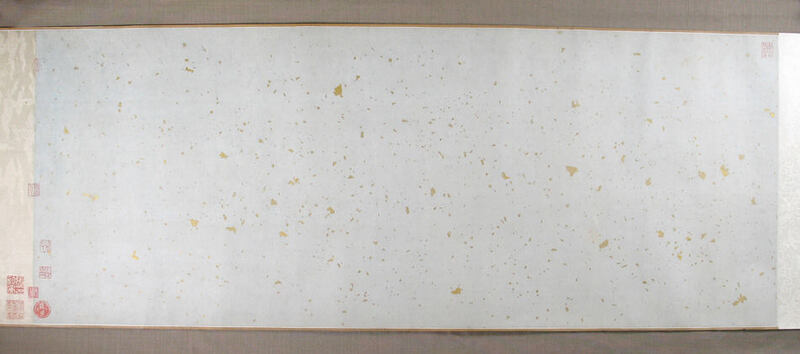

Collectors’ seals

Xiang Yuanbian 項元汴 (1525–1590)

Pingsheng zhenshang 平生真賞

Zuili Xiang shi zhi jia baowan 檇李項氏之家寶玩

Zisun shichang 子孫世昌

Xiang Molin fu miji zhi yin 項墨林父秘笈之印

Tui mi 退密

Molin zi 墨林子

Ruoshui Xuan 若水軒

Jingyin An 淨因菴

Molin 墨林

Molin Zhuren 墨林主人

Xulang Zhai 虛朗齋

Molin miwan 墨林秘玩

Tao li 桃里

Xiang shuzi 項叔子

Xiang Molin jianshang zhang 項墨林鑑賞章

Xiang Yuanbian yin 項元汴印

Zijing fu yin 子京父印

Tianlai Ge 天籟閣

Xiang Zijing jia zhencang 項子京家珍藏

Ji ao 寄敖

Molin Shanren 墨林山人

Zisun yongbao 子孫永保

Wang Shimin 王時敏 (1592–1680)

Wang Shimin yin 王時敏印

Yanke jiancang 煙客鑒藏

Wang Shimin yin 王時敏印

Taiyuan Wang Xunzhi shi shoucang tushu 太原王遜之氏收藏圖書

Gao Shiqi 高士奇 (1654–1704)

Gao shi Jiangcun Caotang zhencang shuhua zhi yin 高氏江村草堂珍藏書畫之印

Xiacheng Zhuren 霞城主人

Gao Dai 高岱 (17th–18th c.)

Tianmen 天門

Zhang Junheng 張鈞衡 (1872–1927)

Wuxing Zhang Junheng Shiming fu shoucang jinshi shuhua beitie shuji yin 吳興張鈞衡石銘父收藏金石書畫碑帖書籍印

Shi Yuan Jushi 適園居士

Shi Yuan zhencang 適園珍藏

Shi Yuan miqie zhi yin 適園祕箧之印

Shi Yuan jiancang 適園鑒藏

Shiming miwan 石銘秘玩

Zhang Junheng 張鈞衡

Shiming kaocang 石銘攷藏

Zhang Shiming jianding fashu minghua 張石銘鑒定法書名畫

Zhang Junheng yin 張鈞衡印

Laizhuo Caotang 來鷟草堂

Wucheng 烏程

Jiang Zuyi 蔣祖詒 (1902–1973)

Miyun Lou 密韵樓

Tan Jing 譚敬 (1911–1991)

He An fu 和菴父

Tan Jing siyin 譚敬私印

Tan Jing 譚敬

Tan shi Qu Zhai shuhua zhi zhang 譚氏區齋書畫之章

Yue ren Tan Jing yin 粵人譚敬印

He An jianding zhenji 龢菴鑒定真蹟

Qu Zhai fu yin 區齋父印

Zhang Heng 張珩 (1915–1963)

Zhang Heng siyin 張珩私印

Zhang shi tushu 張氏圖書

Yunhui Zhai yin 韞輝齋印

Zan de yu ji kuairan zizu 蹔得於己快然自足

Xiyi 希逸

Jiayin ren 甲寅人

Gu Luofu 顧洛阜 (John M. Crawford, Jr., 1913–1988)

Hanguangge Zhu Gu Luofu jiancang Zhongguo gudai shuhua zhi zhang 漢光閣主顧洛阜鑑藏中國古代書畫之章

Unidentified

Dongyi 東簃

Zi yue Yuhe 字曰禹和

Mounter’s seal

Liu Dingzhi 劉定之 (active mid-20th c.)

Gouqu Liu Dingzhi Zhuang 句曲劉定之裝

Xiang Yuanbian 項元汴 (1525–1590)

Pingsheng zhenshang 平生真賞

Zuili Xiang shi zhi jia baowan 檇李項氏之家寶玩

Zisun shichang 子孫世昌

Xiang Molin fu miji zhi yin 項墨林父秘笈之印

Tui mi 退密

Molin zi 墨林子

Ruoshui Xuan 若水軒

Jingyin An 淨因菴

Molin 墨林

Molin Zhuren 墨林主人

Xulang Zhai 虛朗齋

Molin miwan 墨林秘玩

Tao li 桃里

Xiang shuzi 項叔子

Xiang Molin jianshang zhang 項墨林鑑賞章

Xiang Yuanbian yin 項元汴印

Zijing fu yin 子京父印

Tianlai Ge 天籟閣

Xiang Zijing jia zhencang 項子京家珍藏

Ji ao 寄敖

Molin Shanren 墨林山人

Zisun yongbao 子孫永保

Wang Shimin 王時敏 (1592–1680)

Wang Shimin yin 王時敏印

Yanke jiancang 煙客鑒藏

Wang Shimin yin 王時敏印

Taiyuan Wang Xunzhi shi shoucang tushu 太原王遜之氏收藏圖書

Gao Shiqi 高士奇 (1654–1704)

Gao shi Jiangcun Caotang zhencang shuhua zhi yin 高氏江村草堂珍藏書畫之印

Xiacheng Zhuren 霞城主人

Gao Dai 高岱 (17th–18th c.)

Tianmen 天門

Zhang Junheng 張鈞衡 (1872–1927)

Wuxing Zhang Junheng Shiming fu shoucang jinshi shuhua beitie shuji yin 吳興張鈞衡石銘父收藏金石書畫碑帖書籍印

Shi Yuan Jushi 適園居士

Shi Yuan zhencang 適園珍藏

Shi Yuan miqie zhi yin 適園祕箧之印

Shi Yuan jiancang 適園鑒藏

Shiming miwan 石銘秘玩

Zhang Junheng 張鈞衡

Shiming kaocang 石銘攷藏

Zhang Shiming jianding fashu minghua 張石銘鑒定法書名畫

Zhang Junheng yin 張鈞衡印

Laizhuo Caotang 來鷟草堂

Wucheng 烏程

Jiang Zuyi 蔣祖詒 (1902–1973)

Miyun Lou 密韵樓

Tan Jing 譚敬 (1911–1991)

He An fu 和菴父

Tan Jing siyin 譚敬私印

Tan Jing 譚敬

Tan shi Qu Zhai shuhua zhi zhang 譚氏區齋書畫之章

Yue ren Tan Jing yin 粵人譚敬印

He An jianding zhenji 龢菴鑒定真蹟

Qu Zhai fu yin 區齋父印

Zhang Heng 張珩 (1915–1963)

Zhang Heng siyin 張珩私印

Zhang shi tushu 張氏圖書

Yunhui Zhai yin 韞輝齋印

Zan de yu ji kuairan zizu 蹔得於己快然自足

Xiyi 希逸

Jiayin ren 甲寅人

Gu Luofu 顧洛阜 (John M. Crawford, Jr., 1913–1988)

Hanguangge Zhu Gu Luofu jiancang Zhongguo gudai shuhua zhi zhang 漢光閣主顧洛阜鑑藏中國古代書畫之章

Unidentified

Dongyi 東簃

Zi yue Yuhe 字曰禹和

Mounter’s seal

Liu Dingzhi 劉定之 (active mid-20th c.)

Gouqu Liu Dingzhi Zhuang 句曲劉定之裝

Rights Holder

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Identifier

1989.363.29

References

Lee, Sherman E. A History of Far Eastern Art. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, [1964], pp. 291, 402.

Weng, Wan-go, and Thomas Lawton. Chinese Painting and Calligraphy: A Pictorial Survey: 69 Fine Examples from the John Crawford, Jr. Collection. New York: Dover Publications, 1978, pp. 48–49, cat. no. 23.

Suzuki Kei 鈴木敬, ed. Chûgoku kaiga sogo zuroku: Daiikan, Amerika-Kanada Hen 中國繪畫總合圖錄: 第一卷 アメリカ - カナダ 編 (Comprehensive illustrated catalog of Chinese paintings: vol. 1 American and Canadian collections) Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press, 1982, pp. 102–103, cat. no. A15-037.

Shih Shou-ch'ien, Maxwell K. Hearn, and Alfreda Murck. The John M. Crawford, Jr., Collection of Chinese Calligraphy and Painting in the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Checklist. Exh. cat. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1984, p. 21, cat. no. 36.

Fong, Wen C. Beyond Representation: Chinese Painting and Calligraphy, 8th–14th Century. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1992, pp. 418–19, pl. 97.

Gao Shiqi 高士奇. Jiangcun shuhua mu 江村書畫目 (Jiangcun’s catalogue of calligraphies and paintings). Reprinted in Zhongguo shuhua quanshu 中國書畫全書 (Compendium of Classical Publications on Chinese Painting and Calligraphy),. Edited by Lu Fusheng 盧輔聖. Shanghai: Shanghai shuhua chubanshe, 1993–2000, vol. 7, p. 1072.

Yang Zhenguo 杨振国. Haiwai cang Zhongguo lidai ming hua: Liao, Jin, Xixia, Yuan 海外藏中国历代名画: 辽, 金, 西夏, 元 (Famous paintings of successive periods in overseas collections) Edited by Lin Shuzhong 林树中. vol. 4, Changsha: Hunan meishu chubanshe, 1998, p. 102.

Ling Lizhong 凌利中. Wang Yuanqi tihua shougao jianshi 王原祁題畫手稿箋釋 (Annotated research on Wang Yuanqi’s manuscript of painting inscriptions) Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 2017, p. 241, cat. no. 27.

Weng, Wan-go, and Thomas Lawton. Chinese Painting and Calligraphy: A Pictorial Survey: 69 Fine Examples from the John Crawford, Jr. Collection. New York: Dover Publications, 1978, pp. 48–49, cat. no. 23.

Suzuki Kei 鈴木敬, ed. Chûgoku kaiga sogo zuroku: Daiikan, Amerika-Kanada Hen 中國繪畫總合圖錄: 第一卷 アメリカ - カナダ 編 (Comprehensive illustrated catalog of Chinese paintings: vol. 1 American and Canadian collections) Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press, 1982, pp. 102–103, cat. no. A15-037.

Shih Shou-ch'ien, Maxwell K. Hearn, and Alfreda Murck. The John M. Crawford, Jr., Collection of Chinese Calligraphy and Painting in the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Checklist. Exh. cat. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1984, p. 21, cat. no. 36.

Fong, Wen C. Beyond Representation: Chinese Painting and Calligraphy, 8th–14th Century. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1992, pp. 418–19, pl. 97.

Gao Shiqi 高士奇. Jiangcun shuhua mu 江村書畫目 (Jiangcun’s catalogue of calligraphies and paintings). Reprinted in Zhongguo shuhua quanshu 中國書畫全書 (Compendium of Classical Publications on Chinese Painting and Calligraphy),. Edited by Lu Fusheng 盧輔聖. Shanghai: Shanghai shuhua chubanshe, 1993–2000, vol. 7, p. 1072.

Yang Zhenguo 杨振国. Haiwai cang Zhongguo lidai ming hua: Liao, Jin, Xixia, Yuan 海外藏中国历代名画: 辽, 金, 西夏, 元 (Famous paintings of successive periods in overseas collections) Edited by Lin Shuzhong 林树中. vol. 4, Changsha: Hunan meishu chubanshe, 1998, p. 102.

Ling Lizhong 凌利中. Wang Yuanqi tihua shougao jianshi 王原祁題畫手稿箋釋 (Annotated research on Wang Yuanqi’s manuscript of painting inscriptions) Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 2017, p. 241, cat. no. 27.